Laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis

Introduction

Subglottic stenosis is underhand challenging condition for both anatomical and etiological reasons. When considering surgical treatment, stenotic diseases affecting the subglottic region entail an increase in technical issues, principally due to the need of extending the resection to the cricoid cartilage next to the glottis (1). Particular care must be taken when performing resection of the cricoid since the recurrent nerves have access into the larynx at the level of its posterior plate and since the posterior rim of its upper border supports the arytenoid cartilages, which have a crucial role in the vocal function.

Post intubation injuries represent the most common cause of laryngotracheal stenosis. Such injury may be secondary to either orotracheal intubation or tracheostomy (2-4). The damage may involve the glottis, the subglottic region or the trachea itself and is generally the result of prolonged mechanical invasive ventilation through a cuffed tube or cannula. A laryngeal trauma most commonly embroils the posterior region; this could be responsible for subsequent fibrous stricture in the interarytenoid space limiting adduction of the vocal cords. Subglottic lesions usually result in circumferential stenosis of the airway lumen up to a complete obstruction. After tracheostomy, the stenotic tissue may occur at the site of the stoma or at the level of the inflated cuff (4).

Sometimes a scarring stenosis can be discovered in patients without a previous traumatic incident (idiopathic stenosis); it is a rare, potentially progressive condition of uncertain etiology, almost exclusively described in middle-aged women. The disease is often associated with severe inflammation of the vocal cords or the subglottic space and carries a high risk of recurrence. In some patients, history of local infections, collagen diseases and vasculitis have been reported (5).

Others uncommon conditions that can develop in obstruction are cervical trauma, repeated caustics inhalation or high-grade irradiation.

Surgical resection and reconstruction with primary anastomosis represent the first line curative treatment in most subglottic strictures although, in the past years, a number of alternative, less invasive therapeutic options have been proposed.

Alternative treatments

The most popular alternative therapies are represented by rigid bronchoscopy treatments including mechanical dilatation, laser and stenting. Data emerging from literature show excellent functional outcomes after interventional endoscopy in properly selected group of patients affected by post intubation tracheal stenosis, excluding subglottic location (6). These interventional procedures, while safe, play only a limited role in this set of patients due to anatomical and technical aspects (7).

Mechanical dilation alone is rarely successful in restoring an adequate caliber and its benefit is almost always temporary (8). Although laser resections have been widely popularized in the last years for management of various airway lesions, the treatment of subglottic stenosis is generally contraindicated because of the risk for damaging the underlying cricoid cartilage (8). Only a few thin web-like strictures can be successfully managed by laser (usually through a four-quadrant incision) with or without concomitant mechanical dilatation. The benefit in more complex lesions is generally transient and the habit of repeating endoscopic treatment can result in additional tracheal damage with extension of the diseased tract and increased technical difficulty for definitive surgical treatment (7,8). In a large published experience Galluccio (9) included 21 cases of complex subglottic stenosis reporting unsatisfactory results after repeated, variously combined bronchoscopic procedures.

Especially when a stent is placed, this can enlarge the area of damage and be responsible for further complications such as granuloma formation or prosthesis migration (7,10). Similarly, the use of temporary Montgomery T-tube or tracheostomy, which have been widely employed for a long time as a bridge to surgery, can lead to worsening or duplication of the stenotic segment and support bacterial colonization (7), thereby risking compromising access to surgical resection for those patients who are likely to be reconsidered after improvement of general and/or local conditions. Charokopos et al. (11) report results from a series of 12 patients underwent stenting with self-expandable metallic prosthesis for post intubation stenosis (tracheal and laryngotracheal lesions) and conclude that these procedures should be performed only in strictly selected patients unfit for surgery and/or with limited life expectancy.

Perioperative management

Preoperative assessment

Prior to operation, to assess the extent and characteristics of the damaged segment to be resected is crucial in order to determine the best operative approach and anticipate any mobilizing procedures. These informations can be obtained through endoscopic and radiologic examination (4).

Flexible bronchoscopy gains prompt evaluation of the vocal cords function and trophicity, longitudinal extent and severity of the stricture and tracheomalacia. During procedure, some degree of local inflammation may be discovered, especially in patients recently undergoing interventional endoscopic treatments; the presence of active mucosal inflammation at the borders of the stenosis is a local contraindication to surgery and needs stabilization of the scar tissue in order to prevent anastomotic complications (4). Moreover, whenever possible, it is safer to avoid both preoperative and postoperative tracheostomy, since they inevitably result in local chronic immune activation. In the event of infection at the site of a pre-existent tracheostomy, systemic and local antibiotic administration must be introduced and protracted until microbiological sterilization has been proven (7).

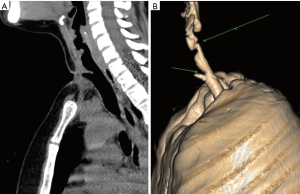

In order to achieve a more accurate evaluation of the tracheal anatomical relationships and tracheal wall status, preoperative neck and chest computed tomography (CT) scan should be performed; (Figure 1) as feasible, high resolution CT scan with three dimensional reconstruction is preferable to standard radiological techniques as it perfectly illustrates the longitudinal extension of the stenosis and its relation with the laryngeal structures (Figure 2) (10).

Anesthesia and postoperative management

At time of intubation in the operative room, some problems may occur in the event of tight stenosis; in that case, preoperative mechanical dilation may be gained by rigid devices or interventional bronchoscopy. Nevertheless, when possible, a traumatic preoperative dilation should be avoided. In most cases of critical stenosis a small caliber (4–4.5 millimeters) endotracheal tube can be passed through the stricture or placed immediately above it, thus ensuring adequate ventilation until the trachea is divided (12). An armored tube is then introduced across the operative field in the distal airway’s stump. Once all the stitches at the anastomotic site have been placed, the cross-field tube is removed and the anesthesiologist (orotracheal or rhinotracheal) tube is advanced onward the suture line resuming ventilation.

Regarding the airway management at the end of the operation, there is no general agreement among surgeons. Some authors recommend proceeding with immediate tracheal extubation in the operative room (13,14), temporarily placing a small uncuffed tube for 48–72 hours whether the patient is not able to breathe spontaneously or presents glottis edema. Some others, including the current authors (12,15,16), prefer to leave the rhinotracheal uncuffed tube temporarily in place in the awakened patient and to pull it out 24 hours later under bronchoscopic check.

In the event that the anastomosis is performed very close to the vocal cords, there is an unpredictable risk of postoperative edema at glottis level. The management of this occurrence is variable, according to the surgeon’s preference. Some authors advice to place an interim small tracheostomy or a Montgomery T-tube distal to the suture line (17), the removal of which is planned according to the status of the glottis and the anastomosis; about that, the present authors prefer to postpone rhinotracheal tube removal by 48–72 hours while administering low-dose steroids, since they have proved that, with this strategy, definitive early extubation can be obtained in almost all patients without further complications (12).

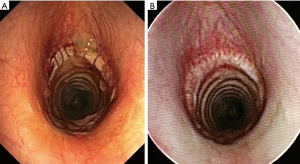

Nevertheless, there is still no general consensus about the use of corticosteroids in the postoperative course. Some surgeons (14) believe that the use of steroids after surgical reconstruction should be avoided and limited only to cases of severe glottis edema with administration of short course high-dose therapy. The current authors (7,12), instead, routinely administer low-dosage steroid therapy in the days following the operation with the aim of reducing glottis edema and mucosal granulation at the anastomotic level; over our long-term experience, no related impairment of the anastomotic suture has been observed. Short and long-term follow-up is principally based on periodic airway assessments by fiberoptic bronchoscopy (Figure 3).

Surgery

Historical notes and technique

The first known experience of thyrotracheal reconstruction after segmental resection of the cricoid cartilage was described by Ogura and Powers in 1964 (18); they reported a series of 7 patients underwent primary anastomosis for subglottic stenosis secondary to blunt injury. For the presence of preoperative complete vocal cords paralysis due to the trauma, however, during these operations no caution to preserve integrity of the recurrent nerves was achieved.

In the early 1970’s Gerwat and Brice (19) developed a technique of preservation of the laryngeal nerves above the level of the crico-thyroid joints by using an oblique line of resection in order to remove only the anterior cricoid arch. Nevertheless, the partial extent of excision of posterior subglottic space has limited the effectiveness of this technique.

The currently in use laryngotracheal resection technique with primary end-to-end anastomosis was first described in 1975 by Pearson and colleagues (20). They proposed a further modification of the previous developed operation that consists in maintaining a shell of the posterior cricoid cartilage thus obtaining a complete resection of the damaged tissues at any level below the vocal cords with respect to laryngeal nerves. With these technical arrangements the upper transection line may pass at a distance of a few millimeters from the vocal cords. Therefore, single-stage thyrotracheal reconstruction can be performed at less than 1 cm below the vocal cords.

The operation is generally managed through a cervical Kocher incision; seldom, a partial median sternotomy can be required. At first, the trachea is sectioned below the stenosis and an armored sterile tube is introduced in the distal airway through the operative field in order to ensure adequate ventilation during the operation. When undergoing isolation of the stenotic tract, the recurrent nerves are generally difficult to identify due to their involvement in the paratracheal fibrotic scar tissue; maintaining circumferential dissection close to the surface of the trachea can be sufficient to avoid nervous damage. The anterior and lateral aspects of the cricoid cartilage are then resected.

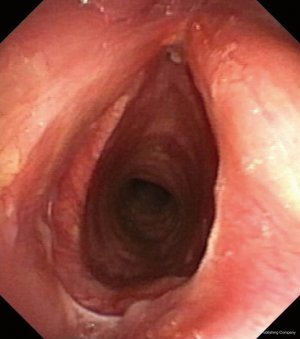

The end-to-end primary anastomosis is performed by interrupted sutures (3-0 or 4-0 absorbable material) in order to compensate the unavoidable caliber discrepancy between the lumen of the subglottic airway and the distal trachea (Figure 4). Pars membranacea plication of the distal trachea permits further offsetting, as suggested by Pearson (20); however, in most cases this expedient may be not necessary since intrinsic elasticity of the trachea may allow adequate compensation. Technical variation may include a running suture for the posterior membranous wall of the anastomosis.

In those patients presenting a thickened interarytenoid space as a consequence of an associated post intubation glottic damage, the complete removal of the redundant tissue is mandatory to obtain an adequate respiratory space and normal vocal cords adduction; in such cases, after the scar excision, the interarytenoid posterior mucosal defect can be covered by a pedicle flap of pars membranacea fashioned from the tracheal stump and created by resecting one or two cartilaginous tracheal rings (21).

When mobilizing the distal airway before reconstruction, the segmental blood supply (which enters the trachea through a series of small, posterolateral branches) must be preserved. For this reason, the tracheal stump should not be isolated circumferentially more than about 1 cm. Excessive devascularization at this level can lead to local ischemic damage with possible anastomotic dehiscence (4).

Alternative reconstruction techniques

In the last decades additional modifications of the thyrotracheal resection technique have been proposed with the aim of obtaining permanent enlargement of the narrow subglottic airway, especially when the glottis space is even involved. These interventions, principally popularized by otolaryngologists, include anterior or anterior and posterior laryngeal split with insertion of a free autologous graft (usually bone or cartilage) between the divided cartilaginous portions.

In 1992 Maddaus et al. (22) described a technique of primary thyrotracheal anastomosis combined with complete laryngofissure and laryngeal reconstruction. After anterior cricoid removal, the thyroid cartilage is transected vertically in the midline to protect the vocal cords and to expose the affected mucosa. The redundant tissue is removed by incising the upper limit of the stenosis with the scalpel. This laryngotracheal reconstruction is indicated for stenosis close to the vocal cords (less than 5 mm).

A different technique generally indicated when the glottis involvement is associated with compromised vocal cords function, has been previously described by Couraud (23). After laryngofissure, the cricoid plate is incised and divided at the midline. Afterward, free graft can be interposed to enlarge the subglottic space. The use of this technique is more frequent in pediatric age or in the event of damage to laryngeal cartilages by previous procedures (laser, tracheostomy, Montgomery T tube, surgery).

In some published experiences high rate of satisfactory results are reported (up to 80%) (24,25). Although, after these procedures, the need for prolonged postoperative stenting is the rule, resulting in impossible decannulation in almost 25% of patients, as recorded by McCaffrey (24).

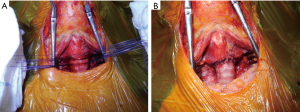

The current authors (26) recently described an original further variation of the Pearson’s technique for the treatment of severe stenosis with involvement of the glottis up to the vocal cords. Once the anterior cricoid arch is removed, a longitudinal median incision of the thyroid cartilage for an extent of about 2 cm (partial laryngofissure) is performed and followed by direct primary thyrotracheal end-to-end anastomosis with some additional technical considerations (Figure 5). After the interrupted sutures are meticulously placed, the margins of the incised thyroid cartilage are retracted laterally and the knots placed at the apex of the fissure incision are tied increasing the caliber of the subglottic space, thus reducing the discrepancy between the anteroposterior and laterolateral axes of the proximal trachea, avoiding a potential ovoid anastomosis (Figure 6). Laryngofissure may also improve access to the posterior mucosa in the immediate subglottic region.

Long segment resections

The maximal length of diseased trachea that can be resected has always been a crucial issue. Most subglottic stenosis involves relatively short segments (1–4 centimeter). Neck bound flexion achieved by placing two strong chin-chest sutures at the end of the operation is generally adequate to minimize tension at anastomosis level (12). Occasionally, longer segments are damaged, often due to reiterated traumatic injuries, repeated endoscopic treatments or placement of temporary Montgomery T-tube or tracheostomy. Increasing technical experience in this field has proved that it is possible to resect and primarily reconstruct up to 50% of the trachea in the adult. Intrinsic elasticity of the tracheal wall, patient’s young age and no history of previous interventional and surgical treatment may positively influence the possible extent of resection. When an extended resection is required, the use of release maneuvers is mandatory in order to avoid excessive tension on the anastomosis and to provide significant technical advantages. Over the years, several techniques of laryngeal (cervical) release and hilar release have been described (27). These procedures can be variably combined during the operation depending on the surgical approach and the extension of the segment to be resected.

The most widely used cervical technique for laryngotracheal stenosis is the Montgomery’s suprahyoid release first described in 1974 (28). It consists in dividing the muscles that insert on the superior aspect of the hyoid bone through a small transverse incision. This maneuver is able to gain up to 2 cm of additional mobility of the proximal stump. The cricothyroid cervical release proposed by Dedo and Fishman (29) has gained a minor consensus because of related higher risk to develop postoperative dysphagia.

Despite its effectiveness in increasing the distal tracheal stump mobilization, the release of the hilum is not routinely used in superior tracheal stenosis because of the need to undergo a second separate thoracic access/incision. This procedure is generally managed through a right thoracotomy or, lately, by a video-assisted thoracic approach (30). At first, the inferior pulmonary ligament is divided to mobilize the right lower lobe and expose the pericardium below the hilum. Pericardial release is performed with a U-shaped incision, starting at the level of the upper pulmonary vein (behind the phrenic nerve) and rising along the posterior hilum up to the pulmonary artery. This allows the carina to advance about 2 cm upward (27). Additional length may be gained by completely incising the pericardium around the hilar structures and/or by dividing the azygous vein.

Results and comments

Since the technical principles for a safe thyrotracheal resection and reconstruction were first described (20), surgical option has been stated to be/represent the best curative treatment for benign subglottic stenosis, allowing definitive and stable high success rate. Long term results from larger published series report good to excellent outcome in more than 90% of patients and low perioperative mortality (less than 2%) (12-14,16,17,31-35). Major surgical complication rates are generally limited, with restenosis rate of 0–11%, anastomotic dehiscence rate of 0–5% and reoperation rate of 0–3% (Table 1).

Table 1

| Author [year] | Pts (n) | Diagnosis | Results | Complications | Restenosis | Dehiscence | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Failure | |||||||

| Grillo [1995] | 62 | PI | 92% | 8% | 12.9% | 8.1%* | 8.1%* | 2.4% |

| Couraud [1995] | 57 | PI, PT, ID | 98.2% (excellent + good) | 1.8% | 3.5% | 0 | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Macchiarini [2001] | 45 | PI | 96% (excellent + good) | 4% | 41% (major + minor) | 4.4% | 0 | 2% |

| Ashiku [2004] | 73 | ID | 91% (excellent + good) | 9% | 17.8% | 9.5% | 0 | 0 |

| Marulli [2008] | 37 | PI, PT, ID | 89% (early); 97% (definitive) | 11% (early); 3% (definitive) | 8.1% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0 |

| Morcillo [2013] | 60 | ID | 98% (excellent + good) | 8,3% (early); 2% (definitive) | 28% (major + minor) | 3.3% | 3.3% | 0 |

| D’Andrilli [2016] | 109 | PI, ID | 91% (early); 99.1% (definitive) | 9% (early); 0,9% (definitive) | 9.2% | 7.4% | 0.9% | 0 |

*, restenosis + dehiscence. PI, postintubation; PT, post-traumatic; ID, idiopathic.

In their wide published experience of more than 500 tracheal resections performed, Grillo and colleagues (31) included results of/from 62 patients underwent thyrotracheal reconstruction, reporting satisfactory or good results in about 89% of cases. In this setting, the anastomosis failure rate was 8.1%; one operative death was reported (1.6%).

In the same years, Couraud et al. (32) published results of a total of 217 patients with benign tracheal stenosis, including 57 patients with subglottic involvement. Results were excellent or good in 98% of cases; there was one perioperative death (1.8%).

Pearson and colleagues (20,22) reported the results of their series including 38 patients treated by the original technique of primary thyrotracheal anastomosis after partial cricoid resection for benign strictures. Recurrence of stenosis occurred in two patients and was successfully managed by reoperation in one case and by laser assisted mechanical dilation in the other case. There was no mortality. Ultimately, therefore, good results were achieved in all patients.

More recently, the increasing technical experience in this field allowed to extend indication to primary laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction to some set of patients previously considered unfit for surgery for general (neurologic disorders) or etiological/local (idiopathic stenosis) reasons.

For a long time, neurological or psychiatric post-coma disorders have been represented a major surgical contraindication (8), due to their poor tolerance of neck flexion and limited collaboration in the early postoperative period.

About that, the present authors (35) have lately proposed long-term results of their series of laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis which include a large group of patients (n=28) with post-coma disorders: results from this group of patients were in line with those observed in the remaining population with no mortality, similar complication rate and success rate. Detailed information of patients and their family about the operation and the postoperative course, intensive perioperative assistance by highly experienced personnel and, whenever feasible, accelerated discharge are inalienable to ensure the best final outcome.

Particular interest has been reported in the literature when considering surgical treatment for idiopathic subglottic stenosis. It is a rare condition of uncertain etiology, almost always associated with severe inflammation of the glottis or the subglottic space. Because of its potential for progression and recurrence, the optimal management and appropriateness of laryngotracheal resection is still debated.

Dedo and Catten (36) analyzed results from their series of 52 patients with idiopathic stenosis variously underwent surgical resection and/or repeated endoscopic procedures (receiving an average of 8 procedures each) and concluded that, for the progressive nature of the disease, treatment should be considered just for palliative purposes.

However, other authors reported good to excellent results in up to 90% of cases with low rates of reoperation (5,13). In a Spanish multi-institutional study on idiopathic stenosis published by Morcillo et al. (17), which includes 60 patients who have received surgical resection with or without postoperative temporary stenting placement, a 97% final success rate is reported with no mortality. In the present authors’ published experience of laryngotracheal resection for subglottic stenosis (35) the definitive success rate was 99%. Out of the 109 patients included in this series, 16 patients were affected by idiopathic disease; in this setting, demanding excision of extra mucosal scar tissue at the level of the cricoid cartilage (posterior plate) was required in most cases with thyrotracheal anastomosis performed close to the vocal cords. In this subgroup of patients early failure rate due to restenosis was 6.3%, however, definitive success rate after endoscopic treatment of the stenosis was 100%. More recently, (February 2017) the current authors experience increases up to 145 operated patients for benign subglottic stenosis, with results in line with those of the before mentioned published series. These data confirm the role of surgery as definitive treatment with stable high rates of success and support our advice that even in patients experiencing early failure of the surgical procedure, final and durable success can still be obtained without reoperation. In this setting, endoscopic procedures can play a crucial role after resection in the management of complicated patients, thus limiting the need for redo surgery.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Marta Silvi for data management and editorial work.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/shc.2017.12.01). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zeeshan A, Detterbeck F, Hecker E. Laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction. Thorac Surg Clin 2014;24:67-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wain JC Jr. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;21:284-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colice GL, Stukel TA, Dain B. Laryngeal complications of prolonged intubation. Chest 1989;96:877-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pearson FG, Andrews MJ. Detection and management of tracheal stenosis following cuffed tube tracheostomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1971;12:359-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grillo HC, Mark EJ, Mathisen DJ, et al. Idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis and its management. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:80-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melkane AE, Matar NE, Haddad AC, et al. Management of postintubation tracheal stenosis: appropriate indications make outcome differences. Respiration 2010;79:395-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ciccone AM, De Giacomo T, Venuta F, et al. Operative and non-operative treatment of benign subglottic laryngotracheal stenosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;26:818-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maddaus MA, Pearson FG. Postintubation injury. In: Patterson GA, Pearson FG, Cooper JD, et al., editors. Pearson’s Thoracic and Esophageal Surgery, 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2008:256.

- Galluccio G, Lucantoni G, Battistoni P, et al. Interventional endoscopy in the management of benign tracheal stenoses: definitive treatment at long-term follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35:429-33; discussion 933-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Andrilli A, Venuta F, Rendina EA. Subglottic tracheal stenosis. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S140-7. [PubMed]

- Charokopos N, Foroulis CN, Rouska E, et al. The management of post-intubation tracheal stenoses with self-expandable stents: early and long-term results in 11 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:919-24. [PubMed]

- D'Andrilli A, Ciccone AM, Venuta F, et al. Long-term results of laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:440-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ashiku SK, Kuzucu A, Grillo HC, et al. Idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis: effective definitive treatment with laryngotracheal resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127:99-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright CD, Grillo HC, Wain JC, et al. Anastomotic complications after tracheal resection: prognostic factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128:731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Couraud L, Chevalier P, Bruneteau A, et al. Treatment of tracheal stenosis after tracheotomy. Therapeutic indications, preparation for the intervention. Apropos of 9 resections in 15 cases of acute respiratory insufficiency. Ann Chir Thorac Cardiovasc 1969;8:791-7. [PubMed]

- Marulli G, Rizzardi G, Bortolotti L, et al. Single-staged laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction for benign strictures in adults. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008;7:227-30; discussion 230. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morcillo A, Wins R, Gómez-Caro A, et al. Single-staged laryngotracheal reconstruction for idiopathic tracheal stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:433-9; discussion 439. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogura JH, Powers WE. Functional restitution of traumatic stenosis of the larynx and pharynx. Laryngoscope 1964;74:1081-110. [PubMed]

- Gerwat J, Bryce DP. The management of subglottic laryngeal stenosis by resection and direct anastomosis. Laryngoscope 1974;84:940-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pearson FG, Cooper JD, Nelems JM, et al. Primary tracheal anastomosis after resection of the cricoid cartilage with preservation of recurrent laryngeal nerves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1975;70:806-16. [PubMed]

- Grillo HC. Primary reconstruction of airway after resection of subglottic laryngeal and upper tracheal stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 1982;33:3-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maddaus MA, Toth JL, Gullane PJ, et al. Subglottic tracheal resection and synchronous laryngeal reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;104:1443-50. [PubMed]

- Couraud L, Jougon JB, Ballester M. Techniques of management of subglottic stenoses with glottic and supraglottic problems. Chest Surg Clin N Am 1996;6:791-809. [PubMed]

- McCaffrey TV. Management of subglottic stenosis in the adult. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1991;100:90-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terra RM, Minamoto H, Carneiro F, et al. Laryngeal split and rib cartilage interpositional grafting: treatment option for glottic/subglottic stenosis in adults. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:818-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ciccone AM, Vanni C, Maurizi G, et al. A Novel Technique for Laryngotracheal Reconstruction for Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:e469-e471. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heitmiller RF. Tracheal release maneuvers. Chest Surg Clin N Am 1996;6:675-82. [PubMed]

- Montgomery WW. Suprahyoid release for tracheal anastomosis. Arch Otolaryngol 1974;99:255-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dedo HH, Fishman NH. The results of laryngeal release, tracheal mobilization and resection for tracheal stenosis in 19 patients. Laryngoscope 1973;83:1204-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lonie SJ, Ch'ng S, Alam NZ, et al. Minimally Invasive Tracheal Resection: Cervical Approach Plus Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:2336-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grillo HC, Donahue DM, Mathisen DJ, et al. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Treatment and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109:486-92; discussion 492-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Couraud L, Jougon JB, Velly JF. Surgical treatment of nontumoral stenoses of the upper airway. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:250-9; discussion 259-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Macchiarini P, Verhoye JP, Chapelier A, et al. Partial cricoidectomy with primary thyrotracheal anastomosis for postintubation subglottic stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121:68-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amorós JM, Ramos R, Villalonga R, et al. Tracheal and cricotracheal resection for laryngotracheal stenosis: experience in 54 consecutive cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:35-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Andrilli A, Maurizi G, Andreetti C, et al. Long-term results of laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis from a series of 109 consecutive patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:105-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dedo HH, Catten MD. Idiopathic progressive subglottic stenosis: findings and treatment in 52 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2001;110:305-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Vanni C, Massullo D, Ciccone AM, D’Andrilli A, Maurizi G, Ibrahim M, Andreetti C, Poggi C, Venuta F, Rendina EA. Laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis. Shanghai Chest 2018;2:3.