VATS thymectomy: oncological results and comparison between minimally invasive strategies

Introduction

Thymectomy consists in complete thymus gland resection and is usually indicated in case of myasthenia gravis (MG) and thymic tumour. Thymectomy is classified in three types of surgical procedures according to the extent of resection. The optimal extent of resection is determined by the gland disease and should influence the best surgical approach to be adopted.

Based on the extent of resection, thymectomies are classified in standard, extended or maximal.

Standard resection consists of the gland alone removal. Extended resection consists of the gland and the surrounding fatty tissue in mediastinum and neck removal. Maximal resection consists of the gland and the complete mediastinal fatty tissue removal until visualisation of recurrent and phrenic nerves is obtained. Maximal thymectomy may also include the opening of one or both the pleural cavities.

The resections mentioned above are performed choosing the best surgical approach among the followings open techniques: cervical incision, partial or total median sternotomy or subxiphoid incision. In the last decades, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has also been introduced in mediastinum surgery, passing from an emerging to a consolidated technique. MIS consists of both unilateral or bilateral video- (VATS) and robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (RATS). Open surgery and MIS can also be combined if necessary.

In this chapter we will address VATS thymectomy for tumours, focusing on oncological results and comparison between others minimal invasive techniques.

Thymus anatomy

The thymus is a gland positioned in the anterior mediastinal compartment. This is a space-delimited anteriorly by the posterior sternal surface, and posteriorly by the superior ventral pericardium and the great vessels. Laterally, anterior compartment is delimited by the two pleural spaces. Thymus size increases until puberty, then decreases by involution. The gland, during adulthood and elderly, reduces to a minimal size but can still be present and active.

Macroscopically, the gland is soft and composed of two lobes H-shaped. However, thymus shape can present different variations. Superiorly the gland is attached to the thyroid by the thyrothymic ligament. Inferiorly thymus extends in front of pericardium towards the phrenic muscle.

Outside of its capsule, many foci of thymic tissue cloud be found in the fatty tissue of the neck to the diaphragm. These islands of thymic tissue location are not predictable.

The arteries to thymus are mainly from the mammary and the inferior thyroid vessel. The arteries directly pass through the capsule into the gland without a hilum. The venous drainage is guaranteed by mammary and inferior thyroids veins and in the most part by a common vein emerging from the two lobes to form one vessel to the innominate vein.

VATS thymectomy indication

The two mains indications for thymus gland resection are MG and thymic tumours.

- MG is classified in thymomatous and non-thymomatous disease. Patients affected by thymomatous MG should always be referred to thymic resection if they are eligible for surgery. In case of non-thymomatous disease, surgery is considered in symptomatic adults younger than 70 years old. Thymectomy rational advantage, in the treatment of MG, should be the removal of antigen stimulation, anti-AChR antibodies and immunomodulation. The best effect offered by surgery should be obtained when the whole gland and any ectopic thymic tissue in mediastinal fat are removed. This statement should prompt to more aggressive surgical approaches but, nowadays, evidence have not been reported.

- Thymectomy by median sternotomy is the most common approach, however many other techniques have been described including MIS. VATS is performed in different variants, including the unilateral three ports technique and the bilateral approach with a cervical incision for extended resection. Results are comparable to open surgery but many advantages regarding postoperative pain, shortens hospital stay, preserved lung function, and better cosmesis are guaranteed.

- In case of thymic tumours or malignancies (thymomas), the standard of care is the achievement of a complete disease resection (R0). Tumor extension or stage determine the feasibility of this goal. The optimal strategy is a whole thymus and surrounding fat tissue en bloc removal, especially in patients with MG. Therefore, an extended or maximal thymectomy is required. In case of aggressive tumour behaviour, gland resection should also include local infiltrations and extra mediastinal disseminations.

The standard technique is median sternotomy because it allows the complete exposure of the mediastinum and both pleural spaces, followed by evaluation of macroscopic capsular invasion, infiltration of perithymic and mediastinal fatty tissue and involvement of surrounding structures (1).

Median sternotomy has been considered the best surgical approach to thymic tumours for decades if in the last years VATS has been introduced in mediastinum surgery as well. To date, the comparison between open and MIS is still a hot topic. Concerning perioperative outcomes, most of the Authors agree that minimally invasive approach guarantees reduced blood loss, shorter surgical and hospital stays, better pain management and fewer complications rate (especially tissue infection) than open surgery.

When we focus on oncological outcomes, results are encouraging as well, but they are not still conclusive. In a review from Friedant et al. (2) in 2016, including 2,038 patients, the authors compared open vs. VATS thymectomy for early stage thymomas and focused on resection completeness and local recurrence rates. They found no statistically significant differences in overall R0 resection and recurrences between the two groups, independently by the stage (Masaoka I or II). Their biases were short-term follow-up and the absence of randomisation to different surgical approach.

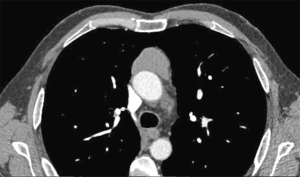

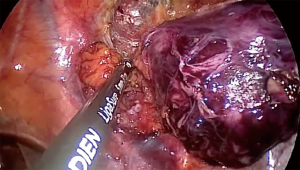

Weksler et al. (3) have published their experience with a small population of patients operated on for early-stage thymomas by VATS or open surgery (Figure 1). In an intermediate-term follow-up, they were able to show the feasibility of MIS and good oncological results comparable with open surgery. Also, Yuan et al. (4) in 2014 reported their experience with 129 cases of Masaoka stages I and II thymoma, confirming that oncological outcomes in VATS were comparable with the classic transsternal approach (Figure 2).

Moreover, Sakamaki et al. (5) reported they experience with a population of 82 cases and results of an intermediate follow-up. They did not find any difference regarding oncologic survival at five years between the two techniques, but overall survival was firmly in favour of VATS group.

The primary challenge in MIS for the thymomatous disease is an indolent tumour behaviour that makes studies with extended follow-up period necessary to assess final oncologic outcomes.

According to the last NCCN guidelines “minimally invasive procedures are not routinely recommended due to the lack of long-term data. However, minimally invasive procedures may be considered for clinical stages I–II if all oncologic goals can be met as in standard procedures, and if performed in specialised centres by surgeons with experience in these techniques” (6).

Also, the ESMO clinical practice guidelines suggest that MIS is an option for presumed stage I and possibly stage II tumours, but should be reserved to skilled and specially trained thoracic surgeons (7).

In summary, MIS, that includes both RATS and VATS, has been advocated as a favourable alternative to median sternotomy open surgery for early-stage thymomas. The choice of MIS should not forget the criteria that are considered determinant also for open surgery the achievement of radical resection. However, it is a fact that many surgeons are adverse minimally invasive approaches underlining that such techniques cloud be associated with increased tumour manipulation, capsular disruption, pleural seeding, incomplete resection, and therefore increased the risk of local recurrence or R0.

Unilateral VATS thymectomy

We usually perform unilateral VATS thymectomy with a tree ports access. Unilateral approach for VATS thymectomy is usually more comfortable from the right side. Indeed, the right chest cavity is more extensive, with a less cardiac obstacle and clear anatomical landmarks such as the superior vena cava. However, the access from the left chest can be considered as well, when requested by the thymoma position, if exclusively positioned on the left side. Tracheal intubation with a double-lumen tube is always recommended to allow selective ventilation when CO2 insufflation is not used.

The patient is positioned on the bed on his back, and the chest side of the access is elevated to a 30° angle with a bump or pillow to have a better opening of intercostal spaces and the plane between the sternum and the gland. The homolateral arm is hanger over the head with a bar. Surgical field preparation includes both the chest side to allow a contralateral access or a quick sternotomy in case of emergency. We always use a 30-degree, 10 mm, thoracoscope with HD camera head. We arrange three, 10 mm, ports protected with a soft tissue retractor. This protects the wound but also allows a painless maximal opening of the port. Ports placement may change, but we usually use 2°, 5° and 6° intercostal space on the middle and anterior axillary line. We are not used to gas insufflation. Anyway, many Authors take advantage of CO2 insufflation to improve access to the surgical field, entirely collapsing the lung and helping in fatty tissue dissection.

Tissue division is performed with an energy device because it works faster and allows comfortable and safe blunt dissection without changing device.

Once entered the chest, the first step is to identify phrenic nerve under the mediastinal pleura. This is the anatomical landmark to start dissection. Mediastinal pleura is then opened above the phrenic nerve from diaphragm to the innominate vein. The nerve should be gently preserved. We start gland mobilisation from the inferior pole dissecting the plane with pericardium because easy to approach and avascular. The thymus is characterised by a greyish-pink colour, while mediastinal fat is yellow. At the end of this step, contralateral pleura and phrenic nerve should appear. Attention is required to avoid contralateral nerve lesion by thermal injury. The cranial part of this dissection is the most dangerous. During dissection, the gland is moved superiorly by a grasp. When the gland is completed dissected from pericardium, we open the pleural reflection between mediastinum and sternum along the internal mammary artery and vein. Now the inferior pole is free, and dissection proceeds superiorly to the innominate vein. This plane is vascular and includes many vein branches to be dissected and controlled (vascular endoclips can be used for larger vessels). To mobilise the upper gland poles, thymus veins, originating from the brachiocephalic vein, must be identified and dissected. Their number varies from 1 to 4 branches originating from the inferior innominate vein side. We usually do a gentle retraction of the gland caudally and contralaterally to expose these veins, and we divide them between clips. Subsequently, we definitively mobilise the upper left pole above brachiocephalic vein using blunt dissection and energy device. Once the thyrothymic ligament is exposed and divided between clips, also on the left side, the thymus is removed from the chest by an endoscopic plastic bag. Lastly, if recommended, all fatty tissue under phrenic nerve and in the aortopulmonary window is removed. We usually insert one chest tube (28 Fr) passing through the ipsilateral pleural space in front of the anterior pericardium. In case of contralateral pleural opening, the chest tube should reach and drain the contralateral pleural space as well.

The disadvantage of unilateral VATS thymectomy is the risk management of contralateral phrenic nerve and superior pole dissection. In case of demanding cases, a contralateral synchronous approach is recommended.

Bilateral VATS thymectomy

Contrary to unilateral thymectomy, bilateral approach permits a better exposure and management of mediastinal structures. It guarantees a safer phrenic nerves dissection and complete removal of fatty tissue. Therefore, bilateral VATS thymectomy is particularly recommended for complete extended resection.

Gland dissection is performed using the same endoscopic devices than unilateral thymectomy. Concerning surgical phases, right side approach and right gland dissection are consistent with unilateral technique. During the bilateral approach, when lower and upper right poles are mobilised, the patient is replaced on right lateral decubitus. Then, we are used to preparing three ports on the left thoracic wall in the same way that the right side. Dissection is done upwards along the left phrenic nerve, mobilising en bloc the lower thymus from the pericardium. Fatty tissue in the aortocaval groove is also wholly dissected.

When all the specimen has been mobilised and dissected, it is removed from the left chest through a port or a utility incision in a plastic bag. Two tubes are placed (in the right and left pleural cavity).

No randomised studies have been published showing the superiority of bilateral approach vs. the unilateral. Nesher et al. (8) in 2012 reported that their experience with contralateral camera surveillance during video-assisted thoracic thymectomy in four patients. They concluded that it was a safe technique to avoid any contralateral nerve injury. Fiorelli et al. in 2016 presented their experience with bilateral VATS extended thymectomy in early stage thymomas. In their study, 23 patients underwent bilateral video-assisted thoracoscopic extended thymectomy, and 20 had thymectomy via sternotomy. They showed that oncological results were consistent with patients whose underwent transsternal extended thymectomy (9).

In our opinion, the bilateral approach should guarantee safer exposure of anatomical landmarks and better fatty tissue removal. However, since no data showed a superiority versus unilateral approach, the approach is mainly on surgeon preferences, with the choice based on their experience and training.

Uniportal VATS thymectomy

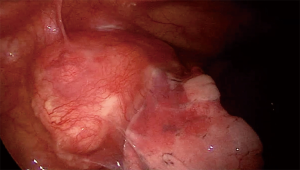

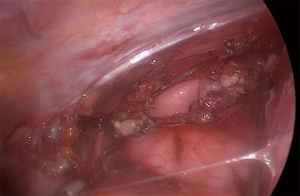

Uniportal VATS thymectomy originates from the current aim to reduce ports number according to the criteria of MIS. It is a difficult technique for skilled surgeons and requires an accurate patients’ selection. As concerning thymomatous disease, indications are limited to <2 cm intrathymic tumour, <4 cm well-encapsulated thymoma or minimally invasive thymoma (10) (Figure 3).

Patient position on the bed is on his back, and chest side of the access is elevated to a 30° angle with a roll placed on the shoulder. The ipsilateral arm should be abducted (hanged on a bar) in order the guarantee an excellent access to the axilla. Chest preparation includes the opposite side to allow contralateral access if necessary or sternotomy. CO2 insufflation (6 L/min flow, 8 mmHg pressure) is required (10). The incision is 3–4 cm in size in the 5th intercostal space. A specific wound retractor enlarges the access without ribs spreading. This device comes with laparoscopic surgery and allows to create pneumothorax (10). A 5 mm, 30-degree lens, the camera is used. Dissection is performed with an energy device for both fatty tissue and small vessels.

The operative steps are like 3 portal unilateral VATS thymectomy. The anatomical landmarks are the right phrenic nerve and the cava vein inferiorly and the mammary artery and vein superiorly. Dissection starts from the lower poles at the pericardial reflection, proceeding to the mediastinum midline and the contralateral pleura. Once the inferior poles have been completed, the thymus is retracted laterally, and dissection goes on cranially. When the gland is mobilised, the upper part is pulled down from the neck to expose the thymic vein for the division. Thymus and fatty tissue are removed by an endo-bag, and the single chest tube is positioned through the incision.

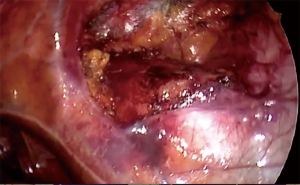

In oncological thymus disease, it is mandatory to avoid any tumour seeding. Therefore, the uniportal technique should be reserved to small or well-encapsulated tumours to allow a complete dissection without any capsule opening (en bloc asportation). Therefore, a no-touch technique is always suggested starting the dissection from the non-tumour gland tissue (Figure 4 and Figure 5). However, a correct patients’ selection by accurate preoperative staging is determinant to obtain favourable oncological results.

The single-port approach is an emerging technique. Therefore, there is only few study published in the literature, about the thymomatous disease.

In 2015, Wu and coworkers (11) published their experience with 29 patients. However, their follow-up was short and not allows oncological conclusions. They showed that this access is feasible and safe, but more data are needed to define its use.

Some Authors have also suggested, as already described for unilateral three ports VATS, the adoption of a contralateral approach to improve mediastinal structures management (12).

To date, we have not enough data to compare unilateral/bilateral vs. uniportal VATS thymectomy. It is our opinion that perioperative endpoints are equivalent or better in favour of uniportal. Further studies are needed to assess oncological value.

RATS vs. VATS

Current guidelines and literature consider MIS a satisfactory alternative to traditional median sternotomy for standard or extended thymectomy in thymomatous disease. Anyway, this approach should be adopted in the early-stage disease when tumour size is small and the disease well-encapsulated. Therefore, this surgery is reserved for Masaoka stages I and II patients.

In 2017 Qian et al. (13) published their experience in a retrospective study enrolling 123 patients with early-stage thymomas. All patients underwent extended thymectomy, and the most common techniques were adopted (median sternotomy, VATS and RATS thymectomy) and compared. Operative time, intra-operative blood loss volume, the occurrence of intraoperative complications, post-operative pleural drainage duration, post-operative pleural drainage volume, duration of hospital stays, and the incidence of postoperative complications were compared between these approaches.

To date, few papers have compared these three approaches at the same time and in the same study. They showed that minimally invasive approaches guarantee better outcomes than median sternotomy regarding perioperative endpoints. This confirms the current trend in literature. Moreover, they were able to show that RATS reduce the postoperative drainage duration and volume and the hospital stay versus the median sternotomy and VATS groups.

Oncological results were also encouraging since, during the follow-up period, all patients survived without any recurrences. These results are consistent with other Authors. For example, in 2013, Ye et al. (14) reported, in a comparative study, no early recurrences during the postoperative follow-up period (17.5 months in the RATS group and 25.2 months in the VATS group).

Conclusions

To summarise our opinion, arising from both personal experience and literature, we underline the following meaningful points:

- Minimal invasive surgery for early-stage (Masaoka I and II) thymomas should always be considered since its feasibility and safety is a comprehensive accepted opinion. Moreover, it allows better perioperative outcomes than open surgery;

- Comparing VATS and RATS among MIS options, robotics could be even more favourable regarding postoperative drainage volume, and therefore hospital is staying;

- Uniportal VATS is still an emerging technique that could guarantee even better results than multiport, but more data are requested to confirm this hypothesis;

- The indolent behaviour of thymomatous disease suggests that further study with a more extended follow-up period is required to determine the oncological value of all MIS techniques in thymomas.

To conclude, we exhort to remember that until meaningful randomised studies comparing the different thymectomy techniques are not available patient’s choice is an essential part of criteria to decide surgical approach.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Lorenzo Spaggiari and Domenico Galetta) for the series “Minimally Invasive Thoracic Oncological Surgery” published in Shanghai Chest. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/shc.2018.01.03). The series “Minimally Invasive Thoracic Oncological Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. LB serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Shanghai Chest from Jun 2017 to May 2019. MS served as the unpaid Associate Editor of Shanghai Chest. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Detterbeck FC, Moran C, Huang J, et al. Which way is up? Policies and procedures for surgeons and pathologists regarding resection specimens of thymic malignancy. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:S1730-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Friedant AJ, Handorf EA, Su S, et al. Minimally Invasive versus Open Thymectomy for Thymic Malignancies: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:30-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weksler B, Dhupar R, Parikh V, et al. Thymic carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of factors predictive of survival in 290 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:299-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan ZY, Cheng GY, Sun KL, et al. Comparative study of video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open thymectomy for thymoma in one single center. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:726-33. [PubMed]

- Sakamaki Y, Oda T, Kanazawa G, et al. Intermediate-term oncologic outcomes after video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy for early-stage thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:1230-7.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas. March 2.2017. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thymic.pdf

- Girard N, Ruffini E, Marx A, et al. Thymic Epithelial Tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 2015;26:v40-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nesher N, Pevni D, Aviram G, et al. Video-assisted thymectomy with contralateral surveillance camera: a means to minimize the risk of contralateral phrenic nerve injury. Innovations (Phila) 2012;7:266-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fiorelli A, Mazzella A, Cascone R, et al. Bilateral thoracoscopic extended thymectomy versus sternotomy. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2016;24:555-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scarci M, Pardolesi A, Solli P. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery thymectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2015;4:567-70. [PubMed]

- Wu CF, Gonzalez-Rivas D, Wen CT, et al. Single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic mediastinal tumour resection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015;21:644-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Arrigo E, et al. Bilateral single-port thoracoscopic extended thymectomy for management of thymoma and myasthenia gravis: case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;11:153. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qian L, Chen X, Huang J, et al. A comparison of three approaches for the treatment of early-stage thymomas: robot-assisted thoracic surgery, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and median sternotomy. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:1997-2005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ye B, Tantai JC, Li W, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in the surgical treatment of Masaoka stage I thymoma. World J Surg Oncol 2013;11:157. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Raveglia F, Bertolaccini L, Solli P, Minervini F, Scarci M. VATS thymectomy: oncological results and comparison between minimally invasive strategies. Shanghai Chest 2018;2:8.